Reducing Information Overload: Ways to Quiet the Information Noise in our Professional Lives

Note: This is the third in a series of thoughts on how we learn in industry and how that’s changing. Check out the first post here.

Arguably, one of the hardest parts about our rapidly changing occupations isn’t learning the new thing that we have to do today, it’s figuring out which of the many new things is the right one for us to do. How is a person supposed to both do his/her job and also vet all the new tools/methods/technologies for practicality and usefulness? Obviously, a single person can’t. We all have our strategies to filter the deluge of information into something more manageable. I want to call out a few big ones and discuss in more detail. There are pros and cons to each, and I think it’s important that we stay mindful of them so we aren’t trapped by them–if we get too used to our shortcuts, we may not be aware when the cons are especially limiting or the pros don’t apply.

Business As Usual

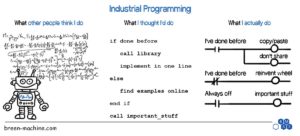

Here’s an easy way to handle all the tech noise: let’s just keep doing things the way we did yesterday and ignore everything else. This is an approach many of us are forced to take due to time and/or budget constraints. For example, I design custom industrial automation, which may give you the impression I’m inventing everything from scratch every time, but that’s not the case. I have to be able to estimate how long a project will take, and work efficiently to stay competitive; staying on schedule and within budget is paramount. The only way to get that predictability is to generally approach things how I’ve done them before. Even when designing custom equipment for an industry I haven’t worked in, I’m mostly using the same templates, the same parts, and the same process.

The simplicity this approach brings is alluring, and indeed we often have no choice, but there are some powerful downsides. I think the most dangerous is that the more we ignore new possibilities, the harder it is to see them when we need to. We develop cognitive shortcuts and lose our creativity. This can go so far that we actively argue against anything new, and try to justify why we do things the way we do, even if the reasons are no longer valid.

Use a Gatekeeper

We know we have to learn some of the new things, but how do we decide which new things are worth our time without exploring all of them? Have someone else do it. Most of us already do this whether we know it or not. Does the guy in the next cubicle always have to have the latest gadget? He’s probably spent a lot of time combing through the tech gadget media, and can help you figure out what makes sense for you. You may ask his opinion before buying your next smartphone or laptop. We identify other people around us that seem to be good at a certain thing, then lean on them to filter the wide world of that thing down to something relevant for us. Tim Ferriss, entrepreneur and author, uses this approach liberally, even basing his political voting choices largely on information filtered through trusted people in his circle.

Specialize

Once there’s too much for one person to do in a society, what happens? People specialize. Fred does the baking, Jill does the tailoring, and Joe the home construction. But with increasing complexity in our jobs, it’s gone way past that. In the field of engineering, for example, there are more specialties than I can count (electrical, mechanical, architectural, chemical, etc). The benefits are obvious. Now, we can selectively ignore most of the world and still do our job well, and society as a whole can function despite the complexity. And the more we specialize, the more we end up being other peoples’ gatekeeper for the things we specialize in.

But there’s always another side of the coin to consider. Specializing requires us to narrow our focus, which can also lead to cognitive shortcuts and the loss of creativity. Increasingly, companies are learning to use multidisciplinary teams for brainstorming and problem-solving to help overcome this limitation.

Gut Check

In the end, there’s always the gut check – the deciding factor that doesn’t need all the facts. Should I pay attention to this new safety relay the salesman is talking about? Is it worth my precious time? Often, there’s no way to know until the time is already spent. So I use that all-deciding, fictional organ called my gut. I like to think this approach is accurate often enough to be useful, but I have no way of confirming that. And that’s the point I really want to establish: It’s important to be aware when we don’t know how effective our systems are, and it’s important to know we’re probably using our guts more often than we realize. Keep an eye out for decisions made in haste or with too little information. The gut can be a powerful ally and an invisible foe.

Tie Them Together

Obviously, no single approach works all the time; we need to use them in tandem. Aside from the “business as usual” approach, they also require some active thought outside of actually doing your job, so we have to set aside some time to self-manage. A knowledge worker can’t just be a worker, he/she has to also be manager. This means tracking deadlines, setting priorities, juggling tasks, and recognizing when something needs a new direction. I’ve found this concept to be invaluable in all aspects of my work, but especially when talking about vaguely defined tasks like continuous learning. For day-to-day work, this might manifest as a nightly routine – before I leave the office, I write down all the things I should do tomorrow and underline the priority. For continuing education, perhaps I set aside a couple hours on the first Monday of every month to ask the question, “What don’t I know that I should, and how can I know it?” The quality of that question obviously determines the quality of the outcome, which brings me to my final point.

The Missing Piece: Mission

What is important? How should I prioritize my time? If I want to stay up to date on new technology, but know I can’t keep up with all of it, how do I choose what goes in my head and what doesn’t? Mission is a concept that’s always been important in an organization, but I’d argue the faster our occupations change, the more essential it is. A mission is a statement that’s both broad and focused, specific and vague. It’s really an attempt at putting a motivating force into words. That motivating force doesn’t change just because there’s a new PLC on the market; it’s not affected by the tech noise in our lives. It stays fairly constant and guides our choices. This is no longer just a business concept; it’s the way by which all our other strategies of selective awareness can work. I’d argue mission is also a key concept in motivating/engaging millennials that’s often misunderstood, but that’s a topic for another post.

Stay tuned!

About the Author

Jon is an engineer, entrepreneur, and teacher. His passion is creating and improving the systems that enhance human life, from automating repetitive tasks to empowering people in their careers. In his spare time, Jon enjoys engineering biological systems in his yard (gardening).