If you run a business in 2022, you’re probably having trouble finding the great people that make your business work. This isn’t new in industrial controls where we’ve had a shortage of qualified workers for decades, and it’s only getting worse. So what can a business do to improve the situation? Take a step back from your immediate needs and ask, “What does the industry need, and what do employees need? Where do controls engineers come from? How can we find/make more? How can we keep them?” I think one answer to all these questions is the same: leadership, training, and a focus on the future. I also think rising to meet these needs will solve your hiring problem.

I’ve been on both sides of the employee/employer relationship, and I’ve worked in a lot of businesses as a consultant and contracted engineer. I’d like to share some of what I’ve seen and how we at Breen Machine Automation Services are working to solve problems and hire good people when nobody else can.

Where do Controls Engineers Come From?

New controls engineers are typically hired with some sort of engineering background, electrical engineering probably being most common. Historically, controls engineers and technicians have bubbled up out of maintenance positions – someone had the knack and started programming a PLC, and now they’re a controls engineer.

There are challenges in both of these paths. Hiring an electrical engineer assures you have someone with foundational knowledge for the position, but little to no background in industrial automation. Hiring a maintenance technician with “the knack” means you get someone who knows industrial automation, but probably has some big holes in foundational knowledge.

How Engineers Learn

Engineering school has only ever been intended as a foundation. It doesn’t teach students how to do a job; it teaches them how to solve generic problems under ideal conditions. Real jobs have always been learned on the job, the most effective examples involving mentorship. With each new project, a young engineer is coached by an experienced engineer to see what’s important in a given task, work efficiently, and avoid pitfalls. This is both powerful and limited. Let’s explore why.

The benefit of this approach is that new engineers get access to the expertise they need on demand. Each new skill and task can be quickly learned in the context of that task. This is ultimately how engineers think and work – specific rules and processes for specific tasks – so the training is a direct model of how to do the job.

The challenges of this approach mostly revolve around time. Experienced engineers’ time is very valuable, so that’s an expensive investment to bring new engineers up to speed. It can also take a long time for enough variety of projects to come around before a new engineer gets all the relevant experience they need to graduate from the mentorship approach. In practice, new engineers often get intermittent mentorship from many people. Nobody’s keeping track of what the new engineer has learned or still needs to learn, each mentor presents different methods, and the learner has to figure out how to stitch all the different methods into their own style and system. This can be a very slow process.

The Solution to Controls Staff Shortages

At the most basic level, the industry needs more controls engineers and technicians. We can make more by improving training throughout the industry – more, better, and more accessible. Universities don’t target such specific job roles, so it’s our responsibility as the employers of controls personnel to do this training. It won’t be easy, but it’s the only way to climb out of this hole, and it brings with it numerous benefits.

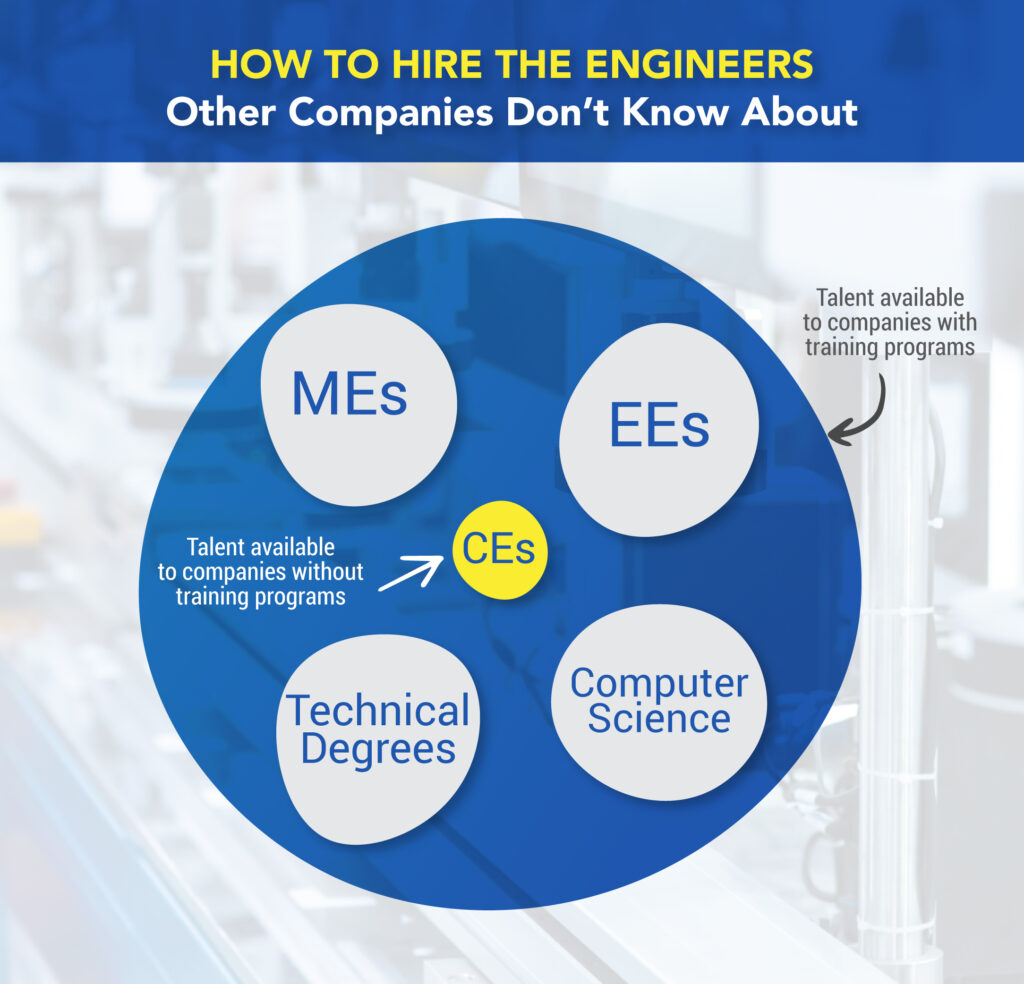

Bigger Talent Pool

Controls engineers are known for being crotchety and unusual. We laugh and hide them from customers, but that’s a real downside of hiring from within the current controls talent pool.

A company that can train new engineers quickly can hire from a larger talent pool. This has been Breen Machine’s approach since its founding in 2016. For example, we’ve hired people with computer science backgrounds. This is a much larger field than controls engineering so we’re able to be pickier about the people we hire. They also tend to have a very strong programming background (that’s what CS is, after all), so they readily pickup PLC and other types of industrial programming. This also gives us the capability to program anything PC or server related, a growing part of industrial automation that most controls engineers have no experience with.

Get What You Want

Hiring an experienced controls engineer can sometimes come with unexpected challenges. A person with experience is a person with a preferred way of doing things, but that doesn’t always fit with their new employer’s needs. I’ve seen a lot of turnover in controls engineering just due to different expectations in programming style and other job activities, rather than any deficiency in actual work quality.

A company that can train their own engineers can engrain whatever work style makes sense. This helps engineers work together more efficiently, makes management and scheduling easier because engineers are more interchangeable, and avoids the effort of trying to unteach bad habits.

Attitude and Aptitude

OK, we’re ready to try hiring and training less experienced controls staff, but how do we select the right candidates if they don’t have 5 years of experience to review? Focus on the things you need that you can’t teach: attitude and aptitude. This is an idea I borrowed from Murray Carter, and it’s worked very well for Breen Machine.

I can teach a person to draw schematics, but I can’t teach them to have the same values as the team at Breen Machine. I have a list of personality traits that I review before every interview, and we ask questions intended to tease these out. For example, we aim to be trusted and valued advisors to our customers. That requires people who are genuine, respectful, truth-oriented, and creative problem solvers. We ask values-related questions in a pre-interview questionnaire to allow prospective employees to really think about these things, then we ask follow up questions and run through scenarios in the interview. This is the “attitude” portion of the process.

When it comes to aptitude, we’re looking for “the knack” – a person who can quickly learn new things and apply them in creative ways. Note that this has very little to do with experience. A person who’s never programmed a PLC before may still be a great candidate if they’re able to quickly learn and do similar things. To this end, we have many little aptitude-related pieces of our interviews, ranging from sudokus to several programming languages, and targeted at understanding how a person learns and thinks, rather than what they know.

Building a Training System

OK, so we know we want to train, and we know how to find candidates. How do we turn them into seasoned engineers/technicians. This is where the rubber meets the road. I want to dispel all the myths I’ve heard in my years in the field. People believe custom automation is too custom to be taught. “You just need years of experience.” But let’s look at this like engineers. Engineers are efficient and effective by following a set process over and over again. This process can be codified and learned.

First, look at the job description and break things into logical chunks. This will vary by position, but I’ll use Breen Machine’s controls engineer position as an example. We do custom and challenging automation projects, so we want our people to have a broad background.

- Electrical design

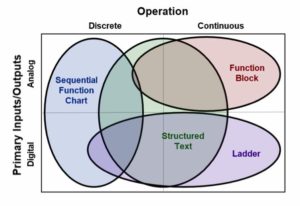

- Programming

- Panel building

- Field wiring

- Troubleshooting

Now break it down even further. For example, “electrical design” is very broad, and too vague to help us train anyone. What does a person actually need to do?

- Power distribution and load sizing

- Schematics

- Panel layout

OK, now we’re getting somewhere. Each of these tasks is trainable. We can sit a new employee down and show them how to do it. Shall we give this bullet list to one of our seasoned employees, sit them down with the new person, and say, “Train this person.”? No! A bullet list is a great start, but it’s not a system. It’s not repeatable or efficient, and it won’t consistently produce the employees we’re looking for.

Each bullet point has to have a consistent process. For example, at Breen Machine, we’ve made a very streamlined system for drawing schematics. We know exactly what goes into the process (BOM, design notes document), we’ve built templates to simplify and speed up the process, we’ve built a library of reusable blocks to drop into those templates, and we’ve written a style guide to keep a consistent feel. This is a system that can be taught, and by putting in the effort up front, we’ve made it easy to teach and efficient for all our engineers to use. Now that we have an efficient system, what’s the next step? We automate, of course!

Automating Training

Engineering time is expensive, so let’s teach this system once, do it well, and record it for future employee training. And we can do way better than PowerPoint. (your employees will thank you) This brings innumerable benefits:

- Trainer’s time spent only once

- Videos can be very organized and have all the fluff edited out for faster training

- Videos can be rewatched as needed

- Training is very accessible, any time, anywhere, at whatever pace makes sense

- Mentor’s time is less interrupted with questions

Breen Machine has published two of our internal video training courses for the rest of the industry to benefit from. We’re very proud of our schematics course “AutoCAD for Industrial Automation,” which encapsulates the whole process described above, templates, reusable blocks, and all. See breen-machine.com/training for more information.

Mentorship

No matter how much formal training you create, mentorship will always play an important role. Just like the “bullet point” rant above, you can’t just assign a mentor to a new employee and expect a consistent, good outcome. Mentorship needs to be intentional and aligned towards real goals. Those goals need to benefit the company and employee, and are the responsibility of both to achieve. This topic deserves a whole book on its own, but for now, here’s a quick breakdown.

- Start by listing the skills you’d like a “full fledged” engineer/technician to have. This is your guide for the rest of the process, and an easy way to keep everyone on the same page.

- Plan for the official mentorship to end. The skills list will help a lot here. Make sure people know when the “new guy” isn’t just the “new guy” anymore. This could be as simple as an announcement at a company meeting, a change in title, or any other public gesture that fits in your company culture. If your company culture is focused around utilitarian discussions (as engineers do), that’s fine too. At Breen Machine, part of this right of passage is the announcement that X person is now ready to take on emergency work for our customers, which typically doesn’t allow room for a mentor to participate.

- If the mentor attends training for any reason, send the mentee with. We eventually want our employees to support each other as equals, rather than mentor-mentee forever, and training together gives them a chance to develop this dynamic.

- Let both the mentor and mentee know that mistakes are expected as part of the learning process and aren’t a sign of failure. The mentee will learn and perform better if they’re not afraid for their job, and the mentor will be less likely to distance from the mentee if mistakes are made.

- Check in monthly with the mentor and mentee, separately, to see how things are going. You’ll learn a lot about your mentorship program, how well it’s working, and what these specific individuals need to succeed.

- Keep the mentee involved in the process. Let them have a say in their own training goals, pacing, and selection of mentor as much as reasonable.

Make It Happen

We’re all in the business of building the things that build things, but what happens when we don’t have enough people to build those things? We need to build those too. There are highly capable people out there looking for a company that’s able and willing to invest in them. We need to stop thinking “5 years of experience” and start thinking “How productive can we help these people be?” By offering quality training to competent people, we’re better able to serve our customers, grow our businesses, and keep doing the things we do best. We also get to tailor our employees work habits to best fit our business needs.

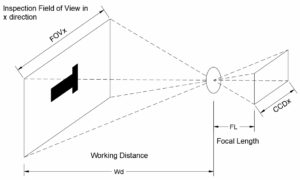

Building a training program will take time and effort, but hopefully this article has provided enough of a guide for you to get started. Don’t reinvent the wheel (or at least not every spoke). Look at existing training resources as you build your program. Consider some of Breen Machine’s free content as a starting point. We’ve released many training videos on YouTube covering machine vision, PLC programming, PLC upgrades, and more. We also write instructional blog posts and have a growing library of training video courses available on our website.

If you’re developing training for your controls staff, get in touch (info@Breen-Machine.com). Together, we can build the people that build the industry.