This post is part of a series of thoughts from BMAS founder/owner Jon Breen on how we learn in industry and how that’s changing. Check out all the posts in our Brain Outside Your Brain series.

How we learn in industry: Limitations of the Human Brain

First, let’s call out the biological brain for what it is. It’s incredibly good at complex pattern recognition, critical thinking, and creativity. In many respects, the world’s biggest supercomputers with the world’s smartest programmers still haven’t matched our biological brains for performance. With this in mind, it’s a little ironic that the rate of technological improvement is so challenging for our brains, pointing out some inherent weaknesses in the biological approach. Namely, learning is slow, we forget things, and we make mistakes. These shortcoming have a major impact on how we learn in industry. Let’s have a look at each one of these in turn.

Learning is Slow

It takes time to push information into our heads, storing patterns for later use. We spend four years getting a degree, learning the foundational patterns for our career (i.e. in engineering we learn mechanics of materials, heat transfer, etc). Then we spend years of on the job training, gaining experience, and keeping up with industry changes. How much time do we spend just learning how to do our jobs? How much does that cost? What activities are cost justified when we consider the cost of learning how to do them?

We Forget Things

Once information is in our heads, if we’re not using it, it fades, releasing neurons to engage in more meaningful pursuits. Ray Kurzweil discusses this process in his book, The Singularity is Near. Memories are stored across many neuron connections, but over time, this number is reduced. “This explains why older memories persist, but nonetheless appear to ‘fade,’ because their resolution has diminished.” I’d argue, of all the many things we learn during a career, most of them quickly fade. For example, I have an intuitive feel for how heat transfer works, but I can’t remember any of the related formulae. I know what a servo motor is and have designed many systems with them, but I couldn’t tell you part numbers, current ratings, or almost any other specific thing about any of them. Of course, the same is true outside of work as well. I know I bought groceries last week because there’s food in the fridge, but I couldn’t tell you what day or what I got. The details are lost quickly while the more general concepts persist for longer. Were the details worth learning in the first place? Does it count as learning at all if it’s presence in our mind is so fleeting?

We Make Mistakes

Even information that we use often is subject to errors. A perfect example is spelling. We all work with the written word every day in one way or another, yet so many people struggle to remember correct spelling. Worse, what happens when we spell something wrong and believe it to be right? This may not be a big issue in most cases for spelling, but small errors can have disastrous results in engineering.

Another Brain Anyone?

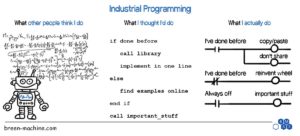

Fortunately, we’ve come up with numerous strategies to combat these shortcomings and improve how we learn in industry. We put the cognitive burden outside of our brain: in a notebook, a calendar, a manual, a spellchecker. In most cases, we structure these resources in a consistent way so all we have to do is remember what a calendar is or understand the idea of a table of contents, and we can quickly retrieve information with perfect accuracy – even if we’ve never seen it before.

Technology has increased the effectiveness of these tools. For example, instead of gathering printed manuals on a shelf for every servo motor I might ever work with, I have instant access through the internet to every manual I might possibly need. Using the search feature in a PDF reader allows me to find information quickly. Indeed, I can even search the entire Internet and the search engine will sometimes pull the relevant information out of the manual and display it on the search results so I don’t have to open the manual. The effectiveness of the “brain outside of your brain” methods continues to improve with technology. I find it amusing that as we develop better computers faster, we simultaneously use them to manage the chaos they bring to our lives. As they say: “Computers. You can’t live with ‘em, you can’t live without ‘em.”

The “brain outside of your brain” approach is pervasive in business and how we learn in industry as well, and it’s gaining more attention than ever before. Ever heard of SOPs (standard operating procedures), VWIs (visual work instructions), or any other TLA (three letter acronym) that makes sense here? These quick reference documents have largely been used to assist manual workers in factories, but I believe a similar approach could benefit knowledge workers as well: Take the time to figure something out, generalize it to apply to other versions of the same thing, then record it in a place where someone else can look it up. With this approach, we can go far beyond the scope of a manual. As a team, we can learn something once and quickly share the information. Some component manufacturers in automation have even started publishing brief how-to videos on the Internet, a perfect example of making one brain’s knowledge easily retrievable by another – a “brain outside your brain.” The industry is dipping its toe into a much bigger pool.

About the Author

Jon is an engineer, entrepreneur, and teacher. His passion is creating and improving the systems that enhance human life, from automating repetitive tasks to empowering people in their careers. In his spare time, Jon enjoys engineering biological systems in his yard (gardening).